Day: March 21, 2023

ALGERIA: The Battle of Algiers: an iconic film whose message of hope still resonates today

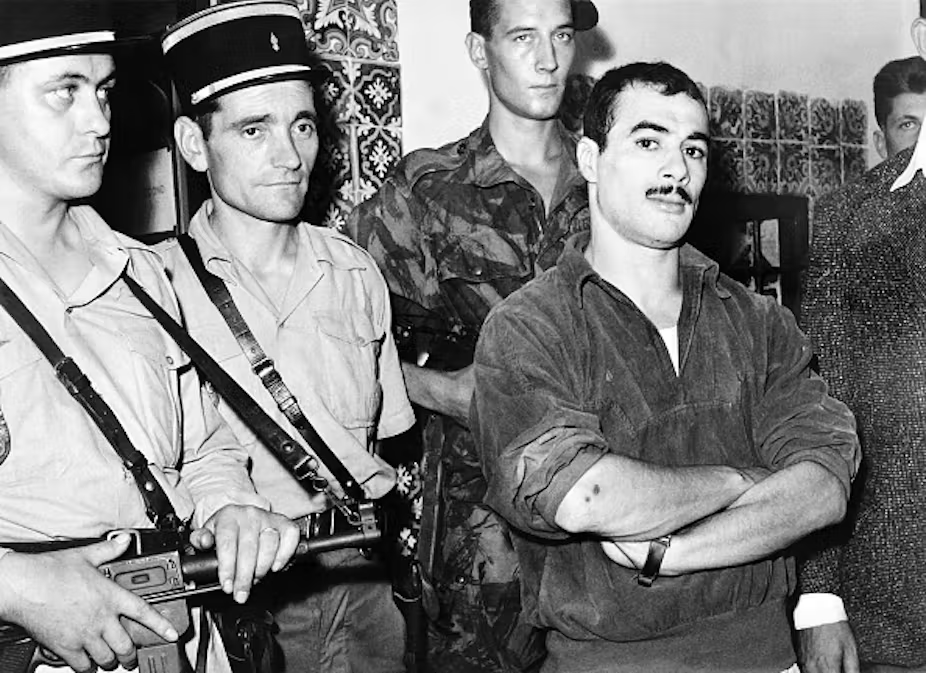

Saadi Yacef, the Algerian revolutionary leader who fought for his country’s liberation from French colonial rule, died on 10 September 2021. Yacef is perhaps one of the better known of Algeria’s resistance fighters because of the role he played in the creation of the film The Battle of Algiers , directed by the renowned Italian film maker Gillo Pontecorvo.

The Battle of Algiers was filmed in 1965 as a co-production between an Italian creative team and the new Algerian FLN (Front de Libération Nationale) government, whose representative Yacef produced the film and stars as the character of Jaffar.

One of the most extraordinary films ever made, The Battle of Algiers is an emotionally devastating account of the anticolonial struggle of the Algerian people and a brutally candid exposé of the French colonial mindset. Many French people were unhappy with the representation of their army and country in the film. It was not officially censored in France , but the general public and all cinemas boycotted it. It was seen as anti-French propaganda.

In later years, the film was screened to groups classed as revolutionaries and terrorists, apparently becoming a “documentary guidebook” in the Palestinian struggle, and for organisations such as the Irish Republican Army and the Black Panthers, who examined its detailed representation of guerrilla tactics.

It was also shown in the Pentagon in 2003, in the middle of the Iraq War. US Counterterrorism experts Richard Clarke and Mike Sheehan suggest that the film showed how a country can win militarily, but still lose the battle for “hearts and minds”.

What relevance does The Battle of Algiers hold today, 55 years after it was first released?

The message of the film is ultimately one of hope: the oppressed multitude will eventually triumph because their cause is just. The images of revolutionary crowds in the film recall the jerky, grainy footage that has emerged from a wave of recent protests in the last decade, from the Black Lives Matter movement to Extinction Rebellion . Pontecorvo thrillingly captures the power and possibility of large gatherings of citizens, who come together to demand rights, putting their bodies at risk to create social and political change.

Additionally, the film refuses to condemn any of the agents in this conflict. As Pontecorvo has stated

in a war, even if from a historical standpoint, one side is proven right, and the other wrong, both do horrendous things when they are in battle.

A film of contrasts

Shot in black and white, the film is difficult to classify in terms of style. Its military action sequences and tactical montages remind us of films like Zero Dark Thirty and The Eye in the Sky; indeed, it is almost impossible to film a scene of politically-motivated torture without having The Battle of Algiers as an implicit or explicit point of reference.

The collective aspect of the film’s creation, and the socialist ideals that inspired it, link it to what’s called Third Cinema. This was a kind of revolutionary cinema, a cinema of the “Third World”, that was designed to overthrow the systems of colonialism and capitalism.

The Battle of Algiers is also an example of Italian neorealism, a major film movement coming out of mid-twentieth century Italy. The neorealists made films that opposed Mussolini’s fascist regime, and they focused on the hardships of the working class in Italy. Neorealism was a moral and aesthetic system: it brought art and politics together to expose the ills of society and bring about social change.

The Battle of Algiers was shot entirely on location in Algiers, and Colonel Mathieu was the only professional on set. Pontocorvo selected the other actors from the local population based on their faces and expressions.

Other elements of the neorealist style was the use of techniques that create a documentary aesthetic such as the hand-held camera. Pontecorvo also uses extracts from real-life FLN and police communiqués, letters, and title cards. And he used newsreel stock, which was cheaper, but also added to the sense of verisimilitude in the film.

Although he believed the Algerians cause to be just, Pontecorvo wanted to create a nuanced and fair account of the war. Therefore, he sets up a series of contrasts to reflect this opposition between French and Algerian. This is present in the original musical score by Ennio Morricone: while groups of French soldiers rampage through the Casbah to the sound of jaunty military drums and horns, a haunting flute theme accompanies sequences which feature Algerian civilians.

Contrast is also evident in the use of light and shadow: there are strong chiaroscuro effects, perhaps reflecting the themes of right and wrong in the film. Pontecorvo also uses shadow to highlight the covert operations of the Algerians: Ali La Pointe’s face is filmed with deep shadows, and the face of Colonel Mathieu is always brightly lit.

Space provides another important contrast in the film. Frantz Fanon, a famous theorist of the Algerian revolution, describes the colonial world as a world “cut in two” because of the stark divide between the coloniser and the colonised. In The Battle of Algiers, the wide boulevards of the European quarter are juxtaposed to the narrow, winding, labyrinthine alleyways of the Casbah. Space is also divided vertically and horizontally – the European quarter is flat, while the Casbah is steep and sloping.

This opposition of space highlights the gap between rich and poor, coloniser and colonised.

The question of bias

The biggest contrast in the film is of course between the French and Algerians. The embodiment of French and European values in the film is Colonel Mathieu. He is a suave figure, confident and controlled in army fatigues, stylish sunglasses and slick speech – he has more dialogue than other characters in the film. A number of critics have argued that Mathieu is far ‘too cool’, given that he is a practitioner and a proponent of torture.

Yet Colonel Mathieu is not depicted as an ogre: above all, he embodies reason. We see this in his statements about the use of torture, when he uses solid rhetorical devices to justify it. He says:

…do you think France should stay in Algeria? If you do, you have to accept the necessary consequences.

This is persuasive as a logical argument – if you want French Algeria, you have to accept the actions that result in this outcome – torture.

If Mathieu and the French have reason, what do the Algerians have?

Firstly, they have raw, visceral emotion and the power of the group. The victory at the end of the film is a victory of the masses, embodied in two figures – the martyr Ali La Pointe, the illiterate everyman who becomes a hero for the revolution, and the gyrating, anonymous Algerian women, whose gaze outwards to the future closes the film.

This takes me to the final point about what the Algerians have on their side – the power of historical right. We see this through Pontecorvo’s use of chronology – the narrative proceeds as a flashback, until we leap forward in time to the euphoria and mania of the end of the war and the triumph of the revolutionaries. Pontecorvo here glosses over the fact that the real Battle of Algiers was lost by the Algerians, and jumps into a future of eventual victory in the war.

This is how he views the process of history – the masses, with moral right on their side, will eventually win.

source/content: theconversation.com (headline edited)

___________

___________

ALGERIA

Arabic Hebrew, Hebrew Arabic: The Work of Anton Shammas. A Palestinian writer, poet and translator of Arabic, Hebrew and English

Within the alienated and antagonist cultures inside Israel’s borders, Arabic and Hebrew—related, but mutually unintelligible languages—cross-fertilize each other.

“Translation” originally meant moving a body. Dead saints and live bishops, for instance, were translated from one place to another. Today, we mostly only use “translation” to mean words transported into other languages, where, unlike bodies, they often change completely.

When Anton Shammas’s Arabesques was first published in 1986, it crossed a notable translational fault line. It wasn’t the first Hebrew-language book written by a Palestinian in Israel, but it became the most famous. The best-seller’s English translation made it to the New York Times’s seven best novels of the year in 1988, but it’s the Hebrew original that drew the attention of scholars Adel Shakour and Abdallah Tarabeih.

“Almost all Israeli Arabs have at least some Hebrew proficiency, and the language is taught in Arab schools,” they explain. “For Israel’s Arab citizens, Hebrew is the key to the dominant Jewish majority and most of its social, financial, and educational resources; it is therefore essential in the minority’s daily life.”

Modern Hebrew is the official language of Israel. The minority Palestinians have a complicated relationship to the majority’s language. Living in Israel means Hebrew is a necessity, but Palestinian identity is intimately connected to Arabic. The language of “Islamic liturgy and the Quran” has a high status among Israeli Palestinians, the majority of whom are Muslim.

“Israeli Jewish society appears to perceive Arab culture as inferior, less modern, and less sophisticated,” write Shakour and Tarabeih, an attitude that includes Arabic. Hebrew, meanwhile, is intimately connected to the identity of Israeli Jews, who in the larger Middle East are a language, religious, and ethnocultural minority.

The fraught relationship between a Jewish state and the non-Jews within it as well as surrounding it, language-wise, meant “Hebrew attained prominence in the non-Jewish literary sphere only in the 1980s, with the works of Anton Shammas, a Christian, and Naim Araidi, a Druze.” (The first Hebrew novel by an Arab, Atallah Mansur’s 1966 In A New Light, proved to be “a fleeting phenomenon.”)

In the press of linguistic intimacies in Israel, the two Semitic—related, but mutually unintelligible—languages cross-fertilize each other, even in the “mutually alienated cultures” found within the state’s borders.

Shakour and Trabeih note that Palestinian “Arabic has borrowed many Hebrew words and even sentences.” Meanwhile, Hebrew, which was revived and modernized in the nineteeth and twentieth centruries, has adopted words from Arabic, as well as a host of other languages including Aramaic, Yiddish, Ladino, Polish, Russian, English, and so on.

Shammas, a noted translator of Arabic into Hebrew (especially of Emile Habibi), is a conscious language bridge-builder between the two languages. Part of this language-bridging means he invents neologisms, new words, in Hebrew.

As Shakour and Tarbeih detail, “Shammas creates new verbal forms in Hebrew by deriving them from nouns along the lines of such derivation in Arabic.” Their first example adds another language to the mix: “the Arabic verb šaksbaranī derived from the noun Shakespeare leads him to use the same derivation in Hebrew.”

Such neologisms can make texts “more obscure” to native readers of a language who have never encountered the word before. Shammas does it to “give the work a highly authentic flavor” to the Arabic culture he wants to introduce to the Jewish Israeli audience.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, some partisans of both Arabic and Hebrew have criticized Shammas’s translations for daring to speak across antagonistic borders. Some Israeli Jews think only Jews can create Hebrew literature. For them, Hebrew is part of the Jewish national character, part of the Zionist project. Some Palestinians think he’s using the enemy’s language, putting a spin on the Italian saying “Traduttore, traditore.”

The saying, meaning “the translator is a traitor,” is usually meant to signify the compromises necessarily made to help language slip across borders into other words. Of course, both languages here, like most languages, are already infiltrated by each other, something language’s border guards never seem to accept.

source/content: daily.jstor.org/JSTOR (headline edited)

______________

______________________________________

AMERICAN / ISRAELI / PALESTINIAN

KUWAIT Airways Breaks Longest Flight Record to New York’s JFK Airport with the A330neo, March 16th, 2023

In line with the airline’s strategy to match capacity with demand, optimize performance with the best in on board experiences for its customers, Kuwait Airways launched its first inaugural flight to New York John F Kennedy Airport utilizing the Airbus A330neo and in setting the record for the longest flight flown by the A330-800 neo in 13 hours.

The award winning Airspace cabin is equipped with a two-class configuration comprising of 32 full flat business class seats and 203 economy class cabin seats on a 2-4-2 configuration. Thus offering passengers state of the art flying experience with more personal space, quietest cabin in its market and the latest generation of in-flight entertainment system and connectivity.

Sustainability

From a sustainability and efficiency standpoint, the A330neo offers benefits to both the airline and the traveling public. With double-digit fuel savings and CO2 emissions compared to other aircraft in its category, the A330- 800 allows significantly lower operational cost and therefore competitive ticket pricing. Captain Ali Al Dukhan, Chairman Kuwait Airways said.

“This flight marks a new era in our strategy to right-fit the best of customer experiences while balancing cost efficiencies and sustainability in our operational decisions. The utilization of this aircraft’s long-range capability will also bring double-digit savings, which coincidentally means less harm to the environment, matching closely to our ESG goals. We are proud to take the next step forward in reaching the corporate strategy goals in reducing costs and enhancing marginal performance”.

Mikail Houari, President, Airbus Africa Middle East said: “We are proud that Kuwait Airways has chosen to deploy the A330-800 on John F Kennedy Airport, a key route for the airline. We are confident that the aircraft will provide passengers with exceptional flying experience while providing the airline with unbeatable economics, efficiency and environmental performance.

source/content: arabtimesonline.com (headline edited)

___________

___________

KUWAIT

SAUDI ARABIA: Winners of King Faisal Prize 2023 Honored in Riyadh

An Emirati, a Moroccan, a South Korean, two Brits and three Americans were honored with the King Faisal Prize 2023.

They served people and enriched humanity with their pioneering work so deserve to be honored and recognized for their distinguished efforts, the King Faisal Foundation said when honoring the winners of the King Faisal Prize 2023.

A glittering award ceremony was held in Riyadh on Monday under the patronage of King Salman, and on his behalf, Prince Faisal bin Bandar, governor of Riyadh Region, attended the ceremony for handing over the King Faisal Prize to the winners this year.

The annual awards are the most prestigious in the Muslim world and recognize outstanding achievement in services to Islam, Islamic studies, Arabic language and literature, medicine and science.

This year an Emirati, a Moroccan, a South Korean, two Brits and three Americans won the prestigious prize, which in its 45th session recognized COVID-19 vaccine developers, nanotechnology scientists and eminent figures in Arabic language and literature, Islamic studies, and service to Islam.

The prize for service to Islam was awarded jointly to Shaikh Nasser bin Abdullah of the UAE and Professor Choi Young Kil-Hamed from South Korea.

The prize for Islamic studies was awarded to Professor Robert Hillenbrand from the UK.

The prize for Arabic language and literature was awarded to Professor Abdelfattah Kilito of Morocco.

The prize for medicine was awarded jointly to Professor Dan Hung Barouch from the US and Professor Sarah Catherine Gilbert from the UK.

In his acceptance speech, Barouch said, “The Ad26 vaccine for COVID-19 demonstrated robust efficacy in humans, even after a single shot, and showed continued protection against virus variants that emerged. This vaccine has been rolled out across the world by the pharmaceutical company Johnson & Johnson, and over 200 million people have received this vaccine, particularly in the developing world.”

Gilbert said that she was “humbled to join the other 2023 laureates, and to follow-in the footsteps of the men and women whose work has been recognized by the foundation for more than four decades. This award is in recognition of my work to co-create a vaccine for COVID-19. A low-cost, accessible, efficacious vaccine that has now been used in more than 180 countries and is estimated to have saved more than six million lives by the start of 2022.”

The prize for science was awarded jointly to Professor Jackie Yi-Ru Ying and Professor Chad Alexander Mirkin, both from the US.

Ying’s research focuses on synthesis of advanced nano materials and systems, and their application in biomedicine, energy conversion and catalysis.

Her inventions have been used to solve challenges in different fields of medicine, chemistry and energy. Her development of stimuli-responsive polymeric nanoparticles led to a technology that can autoregulate the release of insulin, depending on the blood glucose levels in diabetic patients, without the need for external blood glucose monitoring.

“I am deeply honored to be receiving the King Faisal prize in science, especially as the first female recipient of this award,” she said in her acceptance speech.

This year two women scientists have been honored as winners of the King Faisal Prize for medicine and science categories.

The woman behind the Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine, Professor Sarah Gilbert, the Saïd chair of vaccinology in the Nuffield department of Medicine at Oxford University, was honored with the medicine award.

The other woman scientist honored with the King Faisal Prize in science is Professor Jackie Yi-Ru Ying; the A-star senior fellow and director at NanoBio Lab, Agency for Science, Technology and Research. She is a professor at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and was chosen for her work on the synthesis of advanced nanomaterials and systems, and their applications in catalysis, energy conversion and biomedicine.

The King Faisal Prize was established in 1977. The prize was granted for the first time in 1979 in three categories: Service to Islam, Islamic studies and Arabic language and literature. Two additional categories were introduced in 1981: Medicine and science. The first medicine prize was awarded in 1982, and in science two years later.

Since 1979, the King Faisal Prize in its different categories has awarded 290 laureates who have made distinguished contributions to different sciences and causes.

Each prize laureate is given $200,000 (SR750,000); a 24-carat gold medal weighing 200 grams, a certificate inscribed with the laureate’s name and a summary of their work that qualified them for the prize, and the certificate signed by chairman of the prize board, Prince Khalid Al-Faisal.

source/content: arabnews.com (headline edited)

___________

______________________________________

MOROCCO / U.A.E. / SAUDI ARABIA