As he submitted the final maquettes (small-scale models) of Egypt’s folk architecture to the soon-to-open Museum of Folk Arts, Ahram Online spoke to the master himself about the merits and grace of architecture.

To Professor Essam Safi El-Din, architecture is an authentic musical note that resonates with the human touch of the people who conceptualised, built and lived in the building.

Known as the Architect and Tutor who, for over 55 years taught, designed and founded the house of Egyptian Architect and The museum of Folk Arts, Essam Safi El-Din has always believed in the philosophy and grace of popular architecture.

From Shubra Tramway to El-Refaai and Sultan Hassan

“In the 1980s, I designed the pedestrian passage between Sultan Hassan and El-Refaai Mosque, which was originally the tracks of the tramway. So my sketches were inspired by my daily tram ride from Shubra where I lived as a child in 1947 to the Citadel. I copied the same pattern that the tram took from narrow streets that end up in a vast square and the pedestrian area captured the grace and serenity of the architectural gems of the two heritage mosques,” he told Ahram Online.

On revisiting the tramway voyages with open eyes, Safi El-Dien realised that his eyes captured the human wisdom and truth in the details of the buildings that ran by him as the tramway moved across various districts of Cairo.

Handmade Architecture

A child to a renowned architect, Safi El-Din has always been fascinated by designing houses. Making his own handmade maquettes was his passion since childhood. “Since I was seven-years-old I was charmed by architecture and my prize for doing my homework was that I would go to my father’s architecture office and draw with him. My eyes started to watch the buildings and ask who built it and why,” he remembered. This passion was manifested into Egypt’s oldest mockup and design architecture in Egypt and the Arab World.

Passion for Old Buildings

Describing his favorite work spot in his home, Safi El-Din revealed to Ahram Online his relationship with the radio. “Wherever I work, I have two radios to choose from, one set to a music programme and the other to the Quran channel,” he noted

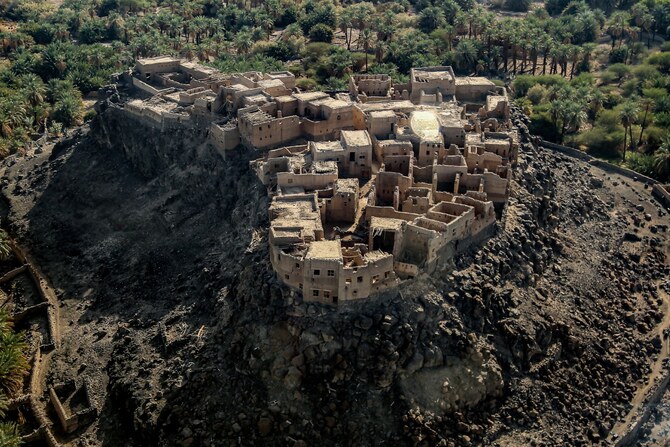

“I was always enchanted by the old architecture because of its beautiful art effects, motifs and language. There is a human and visual dialogue between me and the building because I feel the presence of the head of builders, the builders, and the inhabitants of such building. Old architecture is close to me for it fits the human scale with all its space, physiological and emotional needs,” he explained, describing how buildings can promote serenity and induce better mood for humans.

“You see, architecture is still music, and an architect has to be an artist who has a taste in music,” he explained.

Inspiring Architects

“The architects that have inspired me at an early age are Said Karim whose sketches were the first drawings I have seen in my Dad’s office. I was very fond of Hassan Fathy and Ramsis Wissa Wassef because they have this great sense of belonging to the local building techniques as a mission and a cause,” he added. His passion to safeguard the valuable knowledge in architecture and the grace of local architecture was passed on to all the students he taught and mentored in college throughout the course of over 55 years of academic world. However his keenness to pass on such knowledge to the public made him go the extra mile.

The House of Egyptian Architecture and The National Folk Museum

In the early 1980s, he wanted to document all types of Egyptian architecture under one roof. The Ministry of Culture granted him the current House of Egyptian Architecture. The charming Ottoman-style house that belonged to Hassan Fathy – the father of modern architecture in Egypt – was once the studio of Orientalist artists and has since become a cultural hub, and a museum of local architecture.

Safi El-Din’s maquettes portraying the unique identity of Egyptian architecture were the foundation of The National Folk Art Museum that held its soft opening a few months ago.

Located at the High Institute for Folk Arts in the Haram district, Giza, the official opening date for the museum has not yet been announced.

“The National Folk Art Museum is different from any museum of history because it is not focused just on the historic facts, it is more focused on the cultural value of such items in that era. The value of architecture and its types and how it is comforting. Folk arts as well as folk architecture, reveal the indigenous roots of culture, conduct, the skills of craftsmanship and handicrafts, ” he added.

Essam Safi El-Din’s name resonates with success and authenticity. There is a library dedicated to his works at the British University in Cairo, and he is currently working on a book on his eternal dialogue between architecture and art.

Gems of Wisdom

The most important thing that I have learned is that the value of history is not about knowing the facts, it’s about contextualizing such facts. He stated that his motto in life is a verse from the Quran stating that God will reward all your efforts.

“A person needs to know what his/her mission in life is; why is he here? We need to teach architectural criticism as a subject not a mere cross cutting theme. We need to know the impact of architects on social life and the environment.”

source/content: english.ahram.org.eg

_____________

_________

EGYPT