The Zayed Sustainability Prize, the UAE’s pioneering global sustainability and humanitarian award, has announced this year’s finalists following a deliberation by its esteemed Jury.

The winners will be announced at the Zayed Sustainability Prize Awards Ceremony on 1st December during the 28th Conference of the Parties (COP28) of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, to be held from 30th November to 12th December.

The Zayed Sustainability Prize’s Jury elected the 33 finalists from 5,213 entries received across six categories: Health, Food, Energy, Water, Climate Action and Global High Schools – a 15 percent increase in submissions compared to last year. The new Climate Action category, introduced to mark the UAE’s Year of Sustainability and hosting of COP28 UAE, received 3,178 nominations.

From Brazil, Indonesia, Rwanda and 27 other countries, the finalists represent small and medium sized businesses, nonprofit organisations and high schools, and reflect the Prize’s growing mandate to reward innovations that transcend borders and tackle pressing global challenges.

Dr. Sultan bin Ahmed Al Jaber, Minister of Industry and Advanced Technology, COP28 President-Designate and Director-General of the Zayed Sustainability Prize, said the finalists exemplify the remarkable ingenuity and unwavering commitment to shaping a more sustainable and resilient future for our planet.

Dr. Al Jaber added, “The Zayed Sustainability Prize carries forward the enduring legacy of UAE’s visionary leader, Sheikh Zayed, whose commitment to sustainability and humanitarianism continues to inspire us. This legacy remains the guiding light of our nation’s aspirations, propelling us forward in our mission to uplift communities around the globe. Over the past 15 years, the Prize has been a powerful force for positive change, transforming the lives of over 378 million people across 151 countries. We have incentivised solutions that are driving climate and economic progress in some of the world’s most vulnerable regions.

“This cycle, we received a record-breaking number of submissions from every continent. The innovations put forth by the finalists reflect a profound dedication to inclusivity and an unyielding resolve to bridge critical gaps. These solutions directly align with the four pillars of the COP28 UAE agenda: fast-tracking a just and equitable energy transition, fixing climate finance, focusing on people, lives and livelihoods and underpinning everything with full inclusivity. The work of these sustainability pioneers will contribute practical solutions for climate progress that protect the planet, improve livelihoods, and save lives.”

Through the Prize’s 106 winners to date, 11 million people have gained access to safe drinking water, 54 million homes have gained access to reliable energy, 3.5 million people have gained access to more nutritious food, and over 728,000 people have gained access to affordable healthcare.

Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson, Chair of the Prize Jury, said, “As global challenges continue to mount, our newest group of Prize finalists reveal the extraordinary efforts being made worldwide to meet the needs of the moment with purpose and innovation – inspiring hope for a brighter future. Whether it’s restoring the ocean wilderness, using technology to ensure better, more sustainable farm yields, or driving change for individuals without access to affordable healthcare, these innovators are transforming our world.”

The Health finalists are:

• Alkion BioInnovations is an SME from France that specialises in supplying cost effective and sustainable active ingredients for large-scale pharmaceuticals and vaccines.

• ChildLife Foundation is an NPO from Pakistan that employs an innovative Hub & Spoke healthcare model, linking Emergency Rooms as hubs to telemedicine satellite centres.

• doctorSHARE is an NPO from Indonesia dedicated to expanding healthcare access in remote and inaccessible regions using barge-mounted floating hospitals.

The Food finalists are:

• Gaza Urban & Peri-urban Agricultural Platform is an NPO from Palestine that empowers female agripreneurs in Gaza to achieve food security in their communities.

• Regen Organics is an SME from Kenya that specialises in a municipal-scale manufacturing process that produces insect-based protein for livestock feed and organic fertiliser for horticultural production.

• Semilla Nueva is an NPO from Guatemala that specialises in the development of biofortified maize seeds.

The Energy finalists are:

• Husk Power Systems is an SME from the United States of America that deploys AI-enabled minigrids that provide 24/7 renewable energy to homes, micro enterprises, health clinics, and schools.

• Ignite Power is an SME from Rwanda that specialises in delivering solar powered pay-as-you-go solutions to electrify last mile communities.

• Koolboks is an SME from France that provides off-grid solar refrigeration solutions with integrated Internet of Things (IoT) monitoring for last mile communities, through a lease-to-own sales model.

The Water finalists are:

• ADADK is an SME from Jordan that employs wireless smart sensors that use machine learning and augmented reality for the detection of both visible and hidden water leaks.

• Eau et Vie is an NPO from France that offers individual taps to the homes of impoverished urban residents, ensuring access to clean water in slum areas.

• TransForm is an NPO from Denmark that employs innovative soil filter technology for the cost-effective treatment of wastewater, sewage, and sludge without relying on energy or chemicals.

The Climate Action finalists are:

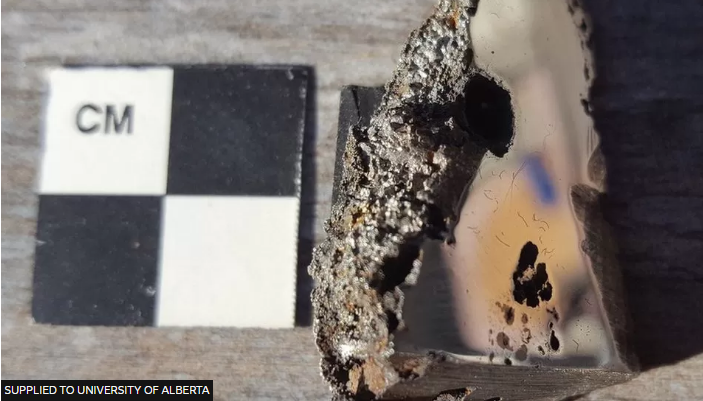

• CarbonCure is an SME from Canada that specialises in carbon removal technology. They inject CO₂ into fresh concrete, effectively reducing its carbon footprint while maintaining performance standards.

• Foundation for Amazon Sustainability is an NPO from Brazil that is dedicated to implementing projects and programmes that advance environmental conservation and empower indigenous communities to protect their rights.

• Kelp Blue is an SME from Namibia that contributes to the restoration of natural ocean wilderness and the mitigation of excess CO₂ by establishing large-scale giant kelp forests in deep waters.

The Global High Schools’ finalists presented project-based, student-led sustainability solutions, with finalists divided into 6 regions. The regional finalists include:

The Americas: Colegio De Alto Rendimiento La Libertad (Peru); Liceo Baldomero Lillo Figueroa (Chile); and New Horizons School (Argentina).

Europe and Central Asia: Northfleet Technology College (United Kingdom); Presidential School in Tashkent (Uzbekistan); and Split International School (Croatia).

Middle East & North Africa: International School (Morocco); JSS International School (United Arab Emirates); and Obour STEM School (Egypt).

Sub-Saharan Africa: Gwani Ibrahim Dan Hajja Academy (Nigeria); Lighthouse Primary and Secondary School (Mauritius); and USAP Community School (Zimbabwe).

South Asia: India International Public School (India); KORT Education Complex (Pakistan); and Obhizatrik School (Bangladesh).

East Asia and the Pacific: Beijing No. 35 High School (China); Swami Vivekananda College (Fiji); and South Hill School, Inc. (The Philippines).

In the Health, Food, Energy, Water and Climate Action categories, each winner receives US$600,000. Each of the six winning Global High Schools receives up to US$100,000.

source/content: wam.ae (headline edited0

_____________

______________________________________________

ABU DHABI, UNITED ARAB EMIRAES (U.A.E)