A small ring around the main artery may cure patients with leaking heart valves. Researchers have documented its effect on animals and they hope they will make it possible to use the technology on humans.

A leaking heart valve – or in technical terms, aortic insufficiency – is a condition in which the valve between the left ventricle of the heart and the main artery cannot close completely. The disease can have varying levels of severity and can be caused by congenital malformations or calcification, among other things.

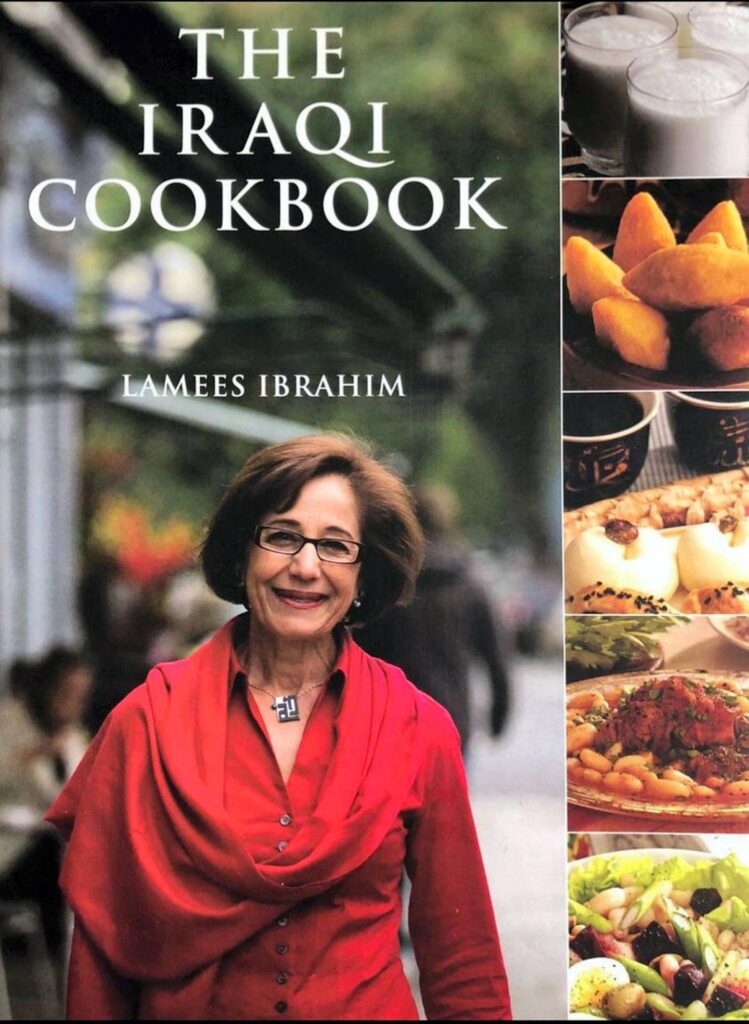

Mariam Noor has developed a small ring that seems to be able to cure leaking heart valves. This can change the way we do cardiovascular surgery. Photo: Lars Kruse, AU Foto.

When the aortic valve leaks, some of the blood returns to the heart, which means the heart has to work harder. In the worst cases, this can lead to heart failure, and this is why it’s important to treat the condition. Doctors usually treat the condition by repairing the diseased heart valve or replacing it with an artificial valve.

Both involve a risk of complications, and therefore engineers from Aarhus University have been working for several years to develop new surgical technology for heart patients.

“A prosthetic heart valve is an effective form of treatment, but it’s also a relatively complicated surgical procedure that brings with it a number of risks and complications in the long term. Now we have found a solution that can make it easier to treat patiens,” says Mariam Noor, a PhD student at the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at Aarhus University and the Department of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Surgery at Aarhus University Hospital.

Ring prevents blood from returning to the heart

Mariam Noor has spent the last three years designing and developing a ring that can give patients with aortic insufficiency good treatment results, and she has invented something that may have impact on the world of surgery.

“Instead of replacing the defective valve, my treatment concept is to enclose it in the main artery so it prevents blood from returning to the heart. I’ve developed a new type of ring that tightens around the aortic root to prevent this,” she says.

In fact, for several years now, cardiologists have been using a type of ring to stabilise the function of the heart valves, but this has not been without its disadvantages.

The traditional ring is round and relatively rigid, and this limits its operation. Furthermore, placing the ring in the body is a challenge because surgeons have to cut the aorta and remove the coronary arteries.

The new ring developed by Mariam Noor is made of an elastic material that can mould itself to the body’s tissue. It also has an opening, which makes it easy to place it correctly.

“The surgical procedure is significantly less invasive, and with the help of diagnostic imaging and 3D printing, we can adjust the ring’s rigidity and strength to the individual patient’s anatomy. This gives us some fantastic options, and the technology has been promising during animal trials,” says Mariam Noor.

Lots of physics in the main artery

Mariam Noor has especially focused on the material properties and design of the ring in order to better retain the dynamics in the cardiovascular system.

“I look at surgical issues through the lens of an engineer, because there’s a lot of physics and mathematics in our cardiovascular system. My approach has been to understand how the aorta works and then transfer this knowledge to design a ring that can recreate normal anatomical conditions in patients,” she says.

The ring consists of a silicone core surrounded by suture-like material. In order to document the effect, in collaboration with her colleagues, Mariam Noor has, carried out her experiments in a heart simulator, whereby it is possible to control the pump function, temperature and flow.

“We can simulate the action of the heart in a very precise environment that closely resembles the human body. This means we can closely study what happens with the ring in the frequency area of every, single heartbeat. It’s been interesting, and we have obtained an incredibly detailed knowledge base to continue working with,” she says.

The researchers have subsequently carried out a costly study to see how the ring expands in the body when the heart pumps, and Mariam Noor was positively surprised.

“We looked at the geometric pattern of the main artery in a pig with a ring and in a pig without it, and we could see that we can actually preserve the natural dynamics. These results look really promising,” she says.

She emphasises that there are a few years’ of clinical approval procedures ahead before the heart ring can benefit patients. (source: Aarhus University)

source/contents: wardheernews.com (headline edited)

__________

_______________________

DANISH / SOMALIAN