The London-born aspiring actress has a deep appreciation for her Moroccan heritage – which may explain why migration is an issue so close to her heart.

Nora Attal has the index finger of one manicured hand extended across the bridge of her nose, and the straightest face she can muster in the circumstances.

It started as an attempt to brush aside the fuss made about her eyebrows, which are, according to various beholders, glorious, serious, stunning, bold, thick, enviable and — somewhat at odds — natural and well groomed.

But now the British-Moroccan fashion model is mulling over a new signature look. “Oh, no! They’re just hair on my face,” Attal tells The National, embarrassed and amused by the attention. “I get them from my Dad — he has very bushy eyebrows.

“If I didn’t groom them, they would be a monobrow. Actually, I saw the film Frida yesterday. It was incredible. I think,” she pauses to regard the mocked-up effect in the zoom camera, “I might just do that … grow a monobrow.”

Perhaps such thinking is to be expected after a 48-hour infusion of cultural rebellion. The day before watching the biopic on the hirsute and indomitable Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, Attal was celebrating turning 23 at her first ever music festival near her home in Spain.

There, she was among the crowd asked by flamboyant American rapper and actress Megan Thee Stallion to make a particular gesture of protest to the US Supreme Court for overturning Roe v. Wade.

“Megan Thee Stallion’s my new icon,” Attal, an enthusiastic gesticulator in daily life, says, “but who I look up to evolves all the time.”

She favours strong, not-so-silent types. Michelle Obama, the former first lady of the US, was top for a while for always telling it as it is — “I still respect her a lot” — along with actor, musician and serial disrupter Riz Ahmed and the Arab writer and women’s rights champion Leila Slimani.

“People like this, I love. I really try to take in their energy,” she says.

It’s a fighting spirit that Attal herself embodied recently when Maria Grazia Chiuri, the creative director of the French fashion house Dior, reportedly said that “models don’t represent women … the model is only a girl who passes in front of you”.

Having walked the runway for Dior 20 times since Chiuri took over, an indignant Attal vented on her Instagram stories, posting: ‘And to hear that I’m not a woman … she is very vocal about her feminism narrative, yet so archaic in thinking that models should only be hangers”.

“Coming into adulthood has been quite nice,” she tells The National. “I understand myself more and, because of modelling, I’ve travelled such a long time alone, experienced a lot, and I’ve maybe grown up quicker.

“I’m definitely more confident, like the way I speak to adults in the industry.”

She recalls being a shy, studious little girl, born in London to two Moroccan parents, Charhabil (Charlie) and Bouchra, and growing up on a council estate in Battersea until the family moved to Surrey.

Sport was an outlet, sometimes whether she liked it or not because of her talent for everything from gymnastics, basketball and tennis to golf and representing her county in long-jump.

Saturday mornings in the house were full of music, regularly featuring Michael Jackson, Prince, Stevie Wonder, and Diana Ross, to whose live performance Attal would dance the night away at a star-studded after party in Marrakech a decade later.

The walls of her childhood bedroom were plastered with magazine covers and fashion campaigns, America’s Next Top Model was the programme of choice, and she would doodle clothes on mannequins in English class instead of writing, say, the set essay on Thomas Hardy.

Yet the industry wasn’t one that young Nora easily identified with or conceived of entering, not least because “there weren’t many people who looked like me”.

“I don’t think she would have ever imagined anything like this,” Attal says, her hands making an all-compassing vertical circle in the air. “Ever, ever, ever.”

It wasn’t long, though, before the striking 12-year-old in blue Converse trainers and a hoodie was first spotted while out in a shopping mall.

“My Dad said ‘yeah, no’ when I went to see the agency,” she remembers with a smile, “and I really appreciate that now …

“It’s tough. I don’t think that young girls should be working in such an adult industry, which doesn’t have a union or HR department that you can go to.”

Modelling, it seems, wasn’t going to take no for an answer. Two years later, the British fashion and documentary photographer Jamie Hawkesworth turned up at her high school, casting for a JW Anderson campaign.

Attal subsequently debuted as Anderson’s muse, dubbed “the mystery girl”, and spent the next few years fitting fashion shows and shoots around education, poring over textbooks while waiting at castings or back stage after hair and make-up.

A fortnight before receiving her A-Level results in History, Psychology and Art at Ewell Castle School, the September issue of British Vogue landed in newsagents with Attal on the cover beside Kate Moss, Edie Campbell, Stella Tennant and Jean Campbell.

The avid true-crime fan was offered a place at Greenwich to study criminology but “took a gap year, deferred it and then dropped it”.

“Working in this industry, I can see that almost anything is possible if you put your mind to it,” she says. “I think everyone should know that.

“My family, being Moroccan, would have loved it if I became a doctor or a lawyer or a pharmacist, and had a normal life but you should do what makes you happy — and you will be successful.”

Represented by Viva Model Management, her own success can be measured by the fact that it would be faster to name the exclusive brands, designers, magazines and celebrity photographers that she hasn’t collaborated with than those she has.

Her brown doe-like eyes, long dark hair and slender 5ft 10in figure quickly became a mainstay on the global circuit in an ascent likened to that of Gigi Hadid.

As with Hadid, she has come to treasure her Mena heritage, and an appreciation has deepened over the years for the hardships that her parents overcame as immigrants “for me to get where I am”.

“It is really important for me to remind myself of that,” she says.

It makes her all the more sensitive to the migration issues prevalent in the UK, particularly the controversial policy of deporting asylum seekers to Rwanda. She has just sent an email opposing the plan to her local MP in England, and urged her 71,000 Instagram followers to do the same.

“I think it’s terrible, I really do. My mum has friends from Syria and Iraq. It could be anyone. Even if you don’t have Syrian friends or Iraqi friends, it’s just a basic human right.”

She talks about what it has meant to have been able to incorporate her North African roots into modelling work many times during a vibrant career.

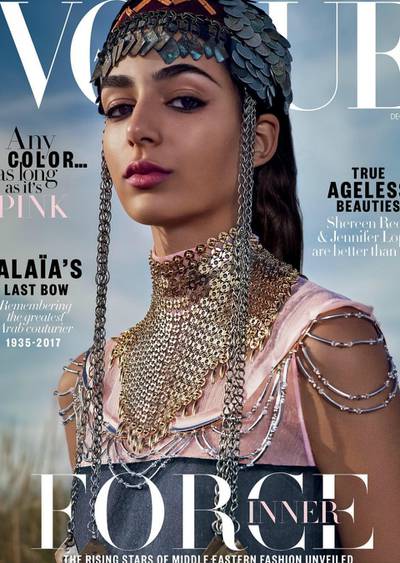

The editor of Vogue Arabia, Manuel Arnaut, described her as “cool, contemporary and a great ambassador of the Arab world” when she graced the December 2017 cover in a Berber ceremonial headpiece.

Among several shoots with the noted American photographer Steven Meisel was one set against the dunes of the Sahara, and she has traversed a catwalk at El Badi Palace in Marrakech.

But perhaps her favourite fashion “story” ever was for a Vogue Italia issue devoted to DNA. The editorial team descended on Attal’s ancestral home in Larache, near Tangier, where she has spent two months every year since she was a toddler.

Her abiding memories of those visits are the aromas of tagine and couscous emanating from the kitchen of her grandmother, Fatna, and forays to the picturesque old town of Chefchaouen in the surrounding hills or along the coastline in search of quiet bays.

This time, though, Fatna lined up in the family living room next to Attal, her brother, Adam, sister, Yesmin, and parents, all dressed top to toe in Chanel for a black and white photo shoot.

“My grandma had never seen anything like it in her life,” she says, fondly. “She thought it was quite strange but was excited. She really loved it.”

More recently, her extended family fronted Ralph Lauren’s holiday campaign for Eid in a video clip that also included Attal’s then fiance, Victor Bastidas, a director and cinematographer 10 years her senior.

The couple met on location at the 16th-century Samode Palace nestled in the ancient Aravalli hills outside Jaipur, but it is all a bit of a blur to Attal now.

What stands out most is being photographed aged 17 by Mario Testino alongside an elephant painted with orange and pink food dye, and embellished in heavy jewellery.

“Arrrgh!,” she says, reliving the excitement and leaning back to show the proximity with her hands. “I shot with an elephant in real life that had to be just here.”

Happily, Bastidas and Attal bonded years later in London over their mutual love for the music written and performed by Thom Yorke for Luca Guadagnino’s supernatural horror film Suspiria, and began dating just before the coronavirus tightened its grip on the world.

Their fairy-tale wedding was held a few months ago at Cortijo San Francisco, a 1,900-square-metre “farmhouse” in Estepona, near Marbella, built as a refuge by the Hollywood actor Stewart Granger who starred in King Solomon’s Mines with Deborah Kerr.

There is a picture from the day of an ornate Mexican fireplace that would have dominated the room until Attal, in strappy skyscraper heels and a breathtaking Lanvin gown, stepped down a narrow passageway into the scene.

The pandemic has marked many other new beginnings for Attal. She did a Run for Heroes in support of the NHS, painted and made lino prints, learnt to cook (pizza, ramen noodles from scratch, a mean carrot cake), and moved to Barcelona for the fresh air and to be closer to nature.

At such a time, it is unsurprising that someone whose favourite poem is William Blake’s Auguries of Innocence — “To see a World in a Grain of Sand. And Heaven in a Wild Flower …” — began to consider the wider picture.

“It was a very big reset. It made me sit down and think about what I wanted to do with my life,” Attal says.

The answer was to act, and she has just graduated from the prestigious Baron Brown Studio in California after two years of studying the Meisner technique over the internet.

Asked if she’s thought much about who she would like to work with, Attal whips out her phone. “Yes, I have lists for everything. A list of directors, of actors, films that I like, references of things.”

For the record, Guadagnino is director number one, leading, in no particular order, Todd Phillips, Pedro Almodovar, Tim Burton, Wes Anderson and the Iranian Asghar Farhadi, “though I don’t speak Farsi, but…,” she says, trailing off hopefully.

Whether theatre or independent film, Attal doesn’t mind. Just having undertaken the training is, she believes, her biggest triumph, which is saying something.

“I’m actually very proud of myself for going back to school, even though it’s on Zoom or it’s not necessarily as heavy as being a doctor.

“I’m doing things that maybe I wouldn’t have done before. I’ve taken the step to tell agents and brands that ‘No, I can’t do that job because I’m studying acting’, and I’m putting my foot down. I think, before, I doubted my abilities, and now I’m like: ‘Yeah, just do it, why not?’”

It is hard not to wonder where Attal’s forthright tendency, fervour and self-determination, so unusual in a young woman in her early 20s, come from.

A clue may lie in a single line buried among the Moroccan press coverage that describes her paternal great-grandfather as a revolutionary, poet and director. The snippet is, it has to be said, uncorroborated, but sounds just about right.

source/content: thenational.ae (headline edited)

___________

pix: Vogue Magazine

_________________________

BRITISH / MOROCCAN