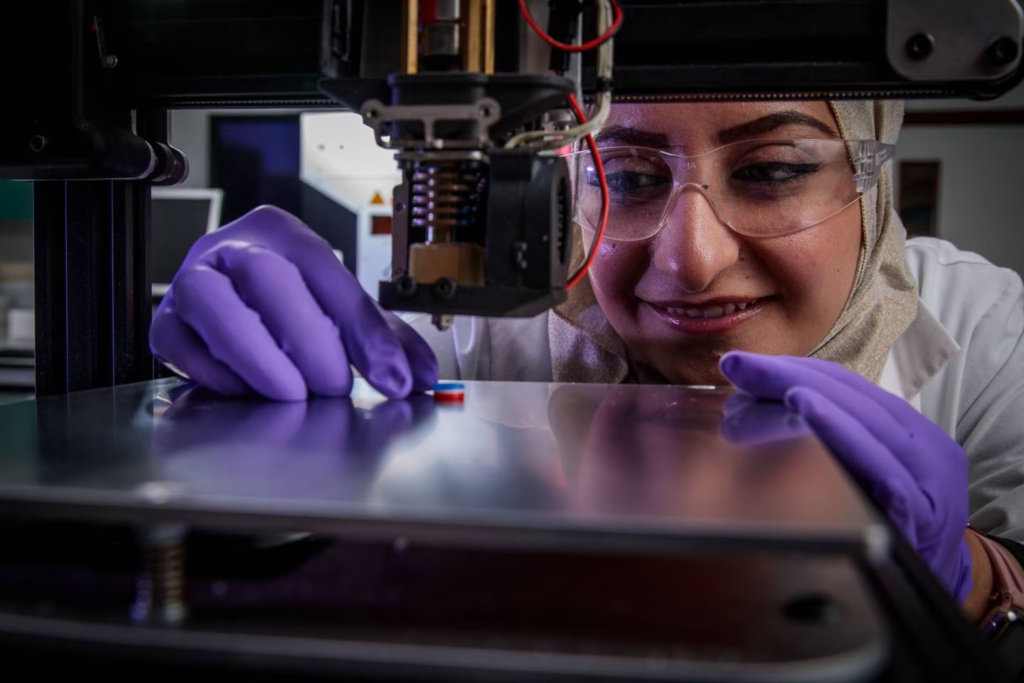

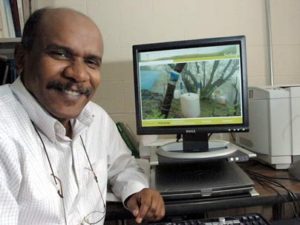

When Dr. Myriam Khalfallah arrived in Vancouver from Tunisia in 2013, she had just earned a bachelor’s degree as an agronomic engineer specializing in fisheries and environment at the National Agronomic Institute of Tunisia (INAT), the University of Carthage. She visited UBC in hopes of meeting Dr. Daniel Pauly, the internationally recognized fisheries scientist—Dr. Khalfallah had used his methods during her engineering practicum work and wanted to meet one of her research inspirations.

The two met, speaking in French, one of Dr. Pauly’s native tongues, before switching to English. He then asked if Dr. Khalfallah mastered scientific Arabic, as Tunisian universities and research institutions are usually French speaking. She did. It turned out that Dr. Pauly needed someone who spoke all three languages to collect fisheries data from Arabic-speaking countries. Dr. Khalfallah landed the job.

“That was the start of the whole thing,” she recalls. “Daniel said, if you do well on this project, maybe I’ll take you as a student. I went back to Tunisia and applied for a work permit and my whole life changed.”

Similarly to most economically developing countries, fisheries data from North Africa, the southern Mediterranean, and the Arabian Peninsula is not always accessible to the international scientific community, notably due to language barriers, publication costs, and funding. Data does exist, but finding it and leveraging it for research takes language skills and to a certain extent a strong personal network. Dr. Khalfallah had both. Her work went well and Dr. Pauly accepted her as a graduate student.

But there was a problem. During her undergraduate studies in Tunisia, a revolution was ignited against the country’s dictatorship. Dr. Khalfallah had been the elected student representative and ombudsperson at her university.

“Tunisia was living under a strict dictatorship at the time,” Myriam says. “We had no right to speak up. The internet was almost fully censored, as were most of the media. Journalists were jailed. It was really awful”.

“I was involved with the demonstrations and doing my best to defend student and human rights. Some professors didn’t understand the role of the student representative and ombudsperson. When I told my professors about the changes that the students wanted, some thought that I was individually calling for change. Obviously, there can be retaliation—when I applied to UBC, my relationships back home made it difficult for me to get into another university.”

Due to her low grades, notably due to the revolution, UBC rejected Dr. Khalfallah’s initial application to graduate school. So Dr. Pauly stepped in.

“Daniel wrote letters for me, as did the dean of my previous university, and a few Tunisian professors, telling UBC they should give me a chance because what happened in Tunisia made things very difficult for everyone.”

The letters of support had the desired effect. Dr. Khalfallah began work on her Master’s of Science degree at UBC’s Institute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability, where she carried on reconstructing fisheries catch data from Arabic-speaking countries, estimating the amount of unreported catch—fish that are caught and not officially accounted for by official statistics.

“Methods used in Western countries aren’t always applicable in the rest of the world,” Dr. Khalfallah notes. “But now there are increasingly newer methods, such as those we use at our research unit, the Sea Around Us , that makes the most of data that is usually overlooked. An interesting part of this work involves collaborating with scientists from all over the world and bridging the gap between data-rich and data-poor regions.”

As her research progressed, she and Dr. Pauly realized that her initial plan—a 17-nation study—was too big for a master’s thesis. So Dr. Khalfallah applied to fast track her research directly to a PhD which required good grades, publications, and strong references.

She defended her thesis on March 26, 2020—the second week of the COVID lockdown when UBC shifted all defenses to Zoom for the first time—and graduated with a PhD in Natural Resource Management and Environmental Studies. After graduation Dr. Khalfallah followed through with post doctorate research, also at UBC, working online to unravel the effects of foreign fishing fleets and aquaculture on West African fisheries.

“Like many scientists then, I was unable to get funding to extend my postdoc as a lot of science funding was going towards medical research and stopping COVID” she says. “Some friends of mine who knew the author Margaret Atwood kindly told her about my postdoc and asked if she knew of anyone who could fund my research. And she offered to do it! She was amazing.”

Dr. Khalfallah currently works with the NGO FHI360 as a marine climate change specialist on the project Sharing Underutilized Resources with Fishers and Farmers (SURF). This project supports Tunisia’s efforts to adapt fisheries and agriculture to climate change and is one of the first of its kind in North Africa to be funded by the U.S. Department of State.

“Climate change is impacting North Africa at a very fast pace,” she says. “Water is getting scarcer by the day. Fishes are moving from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean, replacing native species. In some regions there are almost no fish anymore because overfishing, climate change, and pollution are a very bad combination.”

“I’m trying to either find other, sustainable livelihoods for artisanal fishers, or find a way for them to fish sustainably. Whatever happens in North Africa due to climate change will happen in the rest of the world at certain points. If we can find a way to help them adapt in one way or another, then those ways could potentially be applied in other places where the climate situation deteriorates.”

Dr. Khalfallah recently became a Canadian citizen and lives in Vancouver when not travelling for work. She was recently selected to be one of the alumni representatives of the Faculty of Science at the 2023 Fall Graduation ceremony, 10 years after she first set foot in Canada and UBC.

“I was quite surprised and honored by the invitation and it was an amazing experience.”

For those who have moved here recently and are starting their research career, she has some advice:

“International students have the stress of surviving, often alone, in new foreign environments, all while successfully completing their studies and research; and sometimes it is very difficult to see the light at the end of the tunnel. But I want to say that the light is there. Be persistent and ask for help when needed. Great things are achieved in small steps. Think about just doing one step at a time, and when you look back, you’ll see that you have actually achieved a lot without even realizing it!”

source/content: science.ubc.ca (headline edited)

____________

Myriam Khalfallah, PhD 2020

__________________________

CANADIAN / TUNISIAN